Authorship question: The Case for Mr. Shakespeare

“Who wrote Shakespeare?” is for some a pointless tautology; for others, a question of serious literary enquiry.

Was William Shakespeare just an Elizabethan glover’s son from some provincial backwater? Can it really be the case that the foremost genius of the English language was just a middle-class boy from a small town with only a basic formal education?

Well, actually, considering the lack of available evidence, we can’t even say that for sure…

To date, no records relating to William Shakespeare’s schooling have ever surfaced. It is assumed that when his father, John Shakespeare, was elected to the position of Alderman – in their hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon – that this appointment granted his sons a free education at the local grammar school – but this is by no means certain.

All we can say for sure about William Shakespeare of Stratford was that he was born, died, had children and was embroiled in a number of petty legislative matters. He was married to Anne Hathaway, famously bequeathing to her his ‘second-best bed’ in marginalia of his Last Will and Testament – the same document which conspicuously makes no reference to his books or writings…

To suggest Shakespeare was a mysterious or elusive figure isn’t completely accurate – but it isn’t completely inaccurate either. During his so-called ‘lost years’ (that is, the years from 1585 – 1592), he disappears completely from historical view – the same period when, presumably, he left his wife and children behind him in Stratford, travelled to London and became a successful actor and writer in an improbably short time.

Due to the persistence of a legion of devoted researchers poring over ancient records, the number of documents about Shakespeare continues to grow. However, much of the information they contain is either so dry or at odds with the preconceived notions of Shakespeare’s greatness, that they’re almost irreconcilable. Could the writer of the plays and sonnets, truly be this rascally, possibly non-educated, tax-evading, petty law-breaker that they seem to show?

For many, the slowly building picture of Stratford’s William Shakespeare is simply too hard to square. As a result, a number of other names have been proposed as perhaps ‘more likely’ authorship candidates.

Francis Bacon

For reasons now obscure, after a failed love affair, an American woman, Delia Bacon, became convinced that the Elizabethan lawyer, philosopher and scientist, Francis Bacon, was the ‘true’ Shakespeare. Her only published work – The Philosophy of the plays of Shakespeare unfolded – although only alluding to her namesake as the author of Shakespeare’s plays, did start a precedent for the numerous Shakespeare authorship conspiracy theories that were to follow.

Though, it has to be said, there are certain similarities between some passages in the Shakespeare canon to lines and phrases found in Francis Bacon’s unpublished ‘wastebook’, The Promos, this can only be coincidental because, despite what Baconian theorists would have us believe, Bacon actually hated the theatre and attacked it as a frivolous waste of time in many of his essays. So, unless this was either a baffling subterfuge on his part or he was one of those self-hating playwrights (like, presumably, Ben Elton), it is unlikely that he was Shakespeare.

However, despite this, Bacon’s candidacy as an alternative Shakespeare was expanded upon in Ignatius Donnelly’s The Great Cryptogram, published in 1888.

It is known that Bacon (like Shakespeare) had a keenness for word-play and anagrams – but he also had a penchant for code-breaking and using cipher systems. Donnelly’s book conjectures that the plays of Shakespeare were actually written by Bacon and laced with a series of secret codes revealing their true author.

Using a mathematical cipher popular in Renaissance times – a bizarre formula using prime numbers, logarithms and square roots – Donnelly was able to extract the following message from a Shakespeare text:

Seas ill (Cecil) said that More low (Marlowe) or Shak’st spurre (Shakespeare) never writ a word of them

For Donnelly, the results of this spurious methodology was final clinching proof that Bacon was the writer of Shakespeare’s work – having produced the plays and sonnets to conceal ‘the inner history of his times’.

However, no sooner had Donnelly published his book and professed his findings irrefutable, did a British clergyman, named A. Nicholson, using the exact same methods as Donnelly, found the following in the text of Henry V:

Master Will I Am Shak’st spurre writ the play and was engaged at the curtain

Wow, that must of stung…

Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford

In 1920, a school-master from Gateshead named J. Thomas Looney (a strong name!) first proposed the Earl of Oxford as the writer of Shakespeare in a detailed examination of his work titled Shakespeare Identified.

The book is an attempt to address the perceived wisdom that William Shakespeare – that is, that slavering rustic type from Stratford – lacked the scope and polish to have written the plays attributed to him. They must have been written by an aristocrat, or at least someone who had been to university.

If this was indeed the case, then certainly, the Earl of Oxford seems, on the face of it, like a pretty reasonable alternative author. He was known as a writer of plays and poems, he knew the ways of court, traveled extensively (including, notably, to Verona), and had a connection to Shakespeare’s sponsor, the Earl of Southampton. He also, crucially, (and unlike his erstwhile rival, Bacon) had strong links to the theatre.

It is regrettable for supporters of the theory, then, that Edward de Vere actually died several years before Shakespeare – at a time when he was still seemingly turning out plays. Indeed, many of Shakespeare’s later plays actually contain references to events that the Earl of Oxford never lived to see.

Oxfordians explain this away by suggesting that his ‘later plays’, considered to be collaborations, were in fact reworkings of Oxford’s plays, revised after his death. However, they do struggle to explain how Macbeth (neither collaborative or a ‘later play’) appears to make references to the Gunpowder Plot – which took place in 1605, a year after Oxford’s death.

When Lady Macbeth tells her husband to:

Look like the innocent flower, but be the serpent under’t.

(1.5.74-5)

This is thought to be a reference to a medal which James I had specially commissioned and given to his supporters in the aftermath of November the fifth. The medal’s emblem was a snake amidst flowers.

Where it really falls apart for the Oxfordians is Shakespeare’s dedication in his first published work, Venus and Adonis. The likelihood of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, writing so gushingly to Henry Wriothesly, the Earl of Southampton, is so breathtakingly remote as to render the whole argument ludicrous.

In obsequious, almost groveling, language, Shakespeare, (that is, the writer of the dedication) chastises himself for ‘choosing so strong a prop to support so weak a burden’ – imagining that de Vere, the senior aristocrat of the two men – and Wriothesly’s elder by a good twenty years – would do such a thing is enough to reduce the argument to the absurd.

It also seems unusual that Edward de Vere, who did, himself, support an acting troupe – the Earl of Oxford’s Men – would choose to farm out his best work, under pseudonym, to The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, whilst retaining much middling work for his players…

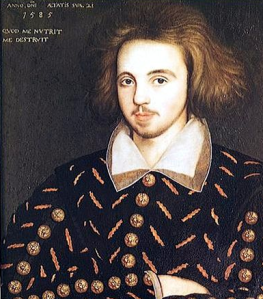

Christopher Marlowe

In 1955, an American journalist named Calvin Hoffman published a book entitled The Murder of the Man who was Shakespeare.

The ‘Marlovian theory’, which Hoffman outlines, proposes that Christopher Marlowe (previously thought to be a brilliant early contemporary and major inspiration of Shakespeare’s) faked his death in 1593 and then wrote the Shakespeare plays and sonnets himself, whilst in exile.

There is certainly some truth in the fact that Marlowe had a lot to run away from. At the time of his ‘death’, he was facing trial on charges of heresy and atheism (on what seems to be fairly reasonable evidence) and would, as a result, probably have not survived long in any case.

In 1593, at the age of 29 (he was two months older than the man from Stratford), Marlowe had already had an exceedingly accomplished writing career, having penned the plays Doctor Faustus, Tamburlaine the Great and The Massacre at Paris – all of which enjoyed considerable commercial success – at a time when Shakespeare was failing to set the theatrical world alight.

On May 30th, with his trial looming and his prospects not looking good, Marlowe decided to go drinking in Deptford. And, like many a night out in Deptford, one imagines, it ended in disaster…

The official line is that Marlowe got in a heated argument over the bar tab, attacked one of his companions with a knife and, in the ensuing struggle, got the blade turned back on him.

To Marlovians, though, this is simply a cover story. They believe that Marlowe faked his death to escape prosecution and continued to write plays under an assumed name – that assumed name was, obviously, ‘William Shakespeare’…

The central claim of the Marlovian theory is that until Christopher Marlowe’s death, there was no writer known as ‘William Shakespeare’. The first time that name appears in connection with his works, seems to be shortly after Marlowe’s death.

Venus and Adonis was registered with the Stationers’ Company on 18 April 1593 (a month prior to Marlowe’s death) with no named author. But when it went on sale on the 12 June (just after Marlowe’s death), Shakespeare’s name had, mysteriously, been added to the cover.

Proponents of the Marlowe theory are quick to point out that if you accept that Marlowe’s death was indeed a sham, the sonnets actually take on a more literal sense.

In Sonnet 25, Shakespeare talks of how cruel fate has denied him the chance to ‘boast of public honour and proud titles’. In Sonnet 75, when Shakespeare mentions a cowardly death coming from ‘a wretch’s knife’ – it had previously, and rather unsatisfactorily, been assumed to be a reference to Death’s scythe.

Similarly, in Shakespeare’s plays, Marlowe’s ghost is never seems far from the scene’s edge.

In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Evans enters singing Marlowe’s famous song ‘Come live with me’. In As You Like It, in an odd addition to what would otherwise be a moment of comic relief, Touchstone intones:

When a man’s verses cannot be understood, nor a man’s good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.

The reference to ‘a great reckoning’ makes this manifestly suggestive of Marlowe’s death.

Of course, it does not necessarily follow that Shakespeare was Marlowe just because of a few oblique references in his plays. A more sober analysis of the available evidence would seem to suggest that Marlowe and Shakespeare were, in fact, different men in the business of producing popular entertainments for similar audiences. However, Marlowe was obviously a massive influence on Shakespeare and remained a massive influence on him.

Whilst Marlowe and Shakespeare’s work may be similar in terms of style, theme and poetic expression, it is quite unalike in terms of characterisation and outlook. Marlowe never wrote any significant female parts in his plays, whilst Shakespeare lacked Marlowe’s trademark gloomy pessimism.

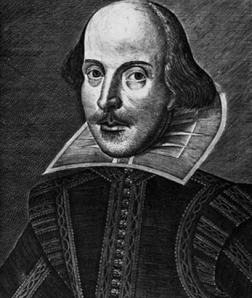

William Shakespeare, the man from Stratford-upon-Avon

Even in his own time, Shakespeare’s modest, provincial background was clearly a source of considerable anguish for him.

In 1592, the pamphleteer and self-proclaimed ‘university wit’, Robert Greene, attacked the young Shakespeare for his conceit – branding him an ‘upstart crow’. Clearly there was something enraging about Shakespeare’s work – because Greene was actually on his deathbed at the time…*

Greene’s book Groatsworth of Wit, Bought with a Million of Repentance (registered 20th September, 1592) openly attacks Shakespeare for having the nerve to compete with him and his university-educated chums.

Greene complains:

Beautified with our feathers, with his tygers hart wrapped in a players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you.

The ‘tygers hart wrapped in a players hyde’ is a play on ‘O tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide’ in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 3.

Though Greene’s intention was obviously to malign Shakespeare, in the long-term he actually did the playwright a tremendous good service – identifying him as a young, non-university-educated author of plays – and actor – before anyone else (so far as we can tell) had committed anything about him print before.

The only artistic outlet of Shakespeare’s that Greene fails to rubbish is his poetry. However, fortunate for posterity, a few years later, Francis Meres, did just that. Author of Palladis Tamia (1598), Meres gives a mixed review of Shakespeare’s work – praising his plays but calling him ‘mellifluous’ and mocking him for passing ‘sugared sonnets among his private friends.’

In the same document, Meres attributes various plays to ‘Will Shakespeare’, including four which were never published in quarto: (Two) Gentlemen of Verona, (Comedy of) Errors, Loves Labours Wonne, and King John. He also identifies plays that were only published anonymously before 1598 – Titus Andronicus, Romeo and Juliet, and Henry IV**. (Unhappily for Oxfordians, Meres goes on to list other writers of note, including ‘Edward, Earl of Oxford’ as a writer of comedy.)

At this time, William Shakespeare was an associated member of the acting company ‘the Lord Chamberlain’s Men’. We can say this with some measure of certainty because on the 15th March 1595, the Treasurer of the Queen’s Chamber paid the acting troupe for performances at court in Greenwich the previous Christmas. The receipt of payment records:

William Kempe, William Shakespeare & Richarde Burbage, servants to the Lord Chamberleyne

Cleary, the aristocratic Bacon and Oxford were not actors (and, in any case, they were both well known in court circles), and Marlowe – assuming he wasn’t dead – was supposed to be in hiding.

On 13th March 1602, John Manningham of the Middle Temple wrote the following anecdote in his journal:

Upon a time when Burbidge played Richard III there was a citizen grew so far in liking with him, that before she went from the play she appointed him to come to her that night unto her by the name of Richard III. Shakespeare, overhearing their conclusion, went before, was entertained and at his game ere Burbage came. Then message being brought that Richard III was at the door, Shakespeare caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard III. Shakespeare’s name William.

The way Manningham really murders the punch-line by qualifying it with Shakespeare’s Christian name, may suggest that the playwright wasn’t especially well-known at the time. Or, possibly, it just says more about Manningham’s ability to tell a gag. (Tellingly, Manningham is one of the few Elizabethan figures whose name has not been put forward as an authorship candidate.) Either way, his diary entry is more documentary evidence of William Shakespeare’s association with Richard Burbage – the principal actor in The Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

In 1618, fellow playwright and poet Ben Jonson made a walking tour of England and Scotland. During this time, he spent two weeks as the guest at the house of the Scottish poet William Drummond – who recorded much of their conversation together. Jonson, being something of a gossip, spent the majority of the time waxing lyrically about the London literati. Though Shakespeare was by this time already dead, Jonson is recorded as being somewhat unkind about his late colleague, suggesting he ‘wanted arte’ and mocking him for foolishly attributing a coastline to Bohemia in The Winter’s Tale.

The ‘First Folio’ (1623) was a compilation of William Shakespeare’s plays put together by Henry Condell and John Hemminges, two actors from his theatre company. By way of an explanatory note, they state:

Without ambition either of selfe-profit, or fame; onely to keepe the memeory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive, as was our SHAKESPEARE, by humble offer his playes.

Ben Jonson also lends his name to the pages. In a long dedicatory verse, he famously refers to the Stratford man as the ‘sweet swan of Avon’ (a fairly unambiguous reference to Stratford, you’d think) and gently mocks him for his lack of education – stating that Shakespeare had ‘small Latin and less Greek’.

All in all, a good deal of Shakespeare’s contemporaries name him as the author of one or more of his plays and sonnets. Including the poets Richard Barnfield and John Weever, the dramatist John Webster and the academic Gabriel Harvey.

The whole anti-Stratfordian mission is simply one of applied snobbishness – a snobbishness which seems hardly to have moved on from the days of Greene and his university wits. Anti-Stratfordians perpetually draw attention to the plays’ portrayal of aristocratic characters and maintain that they couldn’t have been written by this commoner from Stratford. But, of course, this is willfully ignorant of the facts – Christopher Marlowe, son of a cobbler, and Ben Jonson, son of a bricklayer, didn’t write exclusively about members of their fathers’ class – and, yet, no one is suggesting they are not who they say they are…

The death records in the parish registry of The Holy Trinity Church, where William Shakespeare is laid to rest, refer to him simply as ‘Gent’. Of course, predictably, anti-Stratfordians have questioned why this does not read ‘dramatist’ or ‘actor’. In fact, for the Shakespeare family, acquiring a level of respectability was something of a hard-won mission.

In 1568, William Shakespeare’s father, John, applied to the Heralds’ College for a coat of arms – but, falling on hard times, allowed the application to lapse. Twenty years later, his – now successful – eldest son William applied for the coat of arms again. It was granted in 1599. Thereafter, John Shakespeare and his sons were entitled to sign ‘gentleman’ after their name.

The stigma of Shakespeare’s humble origins was obviously something he felt very personally. And, which, despite his best efforts, he never managed to get away from…

~ by wordwrites on February 21, 2011.

Posted in Shakespeare, Shakespeare authorship debate

Tags: 1605, alderman, anne hathaway, anti-stratfordian, as you like it, ateism, baconian, ben elton, calvin hoffman, christopher marlowe, cipher system, ciphers, codes, comedy of errors, delia bacon, deptford, doctor faustus, earl of oxford, earl of southampton, edward de vere, Elizabethan, francis bacon, francis meres, greewich, groatsworth of wit, gunpowder plot, henry iv, henry v, henry vi, heresy, ignatius donnelly, james i, john manningham, john shakespeare, king john, lost years, love's labour won, macbeth, marlovian theory, oxfordian, palladis tamia, quarto, richard burbage, robert greene, romeo and juliet, second best bed, shakespeare, shakespeare authorship, shakespeare authorship debate, shakespeare identified, stratford, stratford-on-avon, tamburlaine the great, the great cryptogram, the lord chamberlain's men, the massacre at paris, the merry wives of windsor, the murder of the man who was shakespeare, the promos, the sonnets, titus andronicus, two gentlemen of verona, upstart crow, venus and adonis, william shakespeare

What of William Henry Ireland? Sure his Vortigen was windy nonsense, rambling fuck-wittery with a tin ear, impossible to perform and harder to listen to. But…he could have been having an off day…

Let’s not rule out Montague John Druitt. He had pebbles in his pockets and there was a history of insanity on his mother’s side. I wonder what my old friend Edward Fido would make of it?

I mean MARTIN Fido. I’m not worried about what the start CITV’s “Woof!” thinks about Shakespeare. Though he IS on the telly and therefore much better than me in all ways.